Why the .25-45 Sharp is likely the best new "AR" Round

Why the .25-45 Sharp is likely the best new "AR" Round

So, there's been quite a few new AR rounds out there or, .223 replacements. The 6.5mm Grendel, the 6.8mm Remington, the .300 black-out, the .458 SOCOM (which is actually an old round, but it's making a come-back) and numerous others designed to work inside of a gun more or less designed to fire the .223 or 5.56mm x 45mm NATO, without many modifications. The receiver of the gun, the legal part of the gun, and arguably the hardest part to make and recreate, can be used as well as the magazines with all these rounds, but the bolt, the recoil spring and the barrel often need to be replaced, which are fairly easy to replace on most firearms. Especially with the AR, which has an easily detachable barrel, it's easy modify these weapons to be able to accept and fire the rounds by changing out the bolt, the spring and the barrel. In the case of the .300 black-out and .25-45 sharps, all that needs to be replaced is, the barrel. According to some however, the .25-45 sharp is the worst new AR round, and the Mk. 262 far surpasses it and the 6.8mm Remington. I simply disagree.

What makes the .25-45 Sharps so promising is that unlike the 6.8mm Remington or 6.5mm Grendel which are objectivity more powerful and longer range rounds, is as mentioned before, that only the barrel needs to be replaced. Designing, creating and fitting in an entirely new bolt and recoil spring is apparently rather difficult for most firearms manufacturers, albeit theoretically possible. The ACR, or Remington Advanced Combat Rifle, was originally promised to be chambered in numerous rounds, from the 6.8mm to the 7.62mm x 39mm, but never was actually mass produced in any caliber other than the 5.56mm. After over 5 years since being announced, the 7.62mm x 51mm NATO and other variants of the rifle have yet to come to fruition, and seem to be little more than vapor ware. The FN SCAR, Tavor and numerous other companies have promised caliber version after caliber version, and as of yet only a single 6.5mm Grendel and a handful of 6.8mm Remington firearms even exist for sale, largely AR-15 variants. Apparently designing a new bolt, which is simple in theory, is far more complicated in practice. Likely, the size of the new rounds means the bolts have to be enlarged and a new hole has to be drilled in the bolt carrier to fit the new balanced bolt, or the bolt has to be asymmetrically placed which would put a lot of stress on the gun and possibly limit reliability. It's far more likely that company executives simply did a tally of the popularity of the cartridge, realized the profits wouldn't be worth the money spent and scrapped the project after they realized their money could be better spent for higher profits. Gun manufacturers are a finicky lot, and with every gun ban scare you get huge fluctuations in prices from ammo to guns, manufacturers changing processes even before the ban gets passed (which it might actually never), company head quarters changing and generally the tiniest tremors, like a pebble in a pond, can create gigantic shock waves through the industry. Most likely, as no other company was producing rifles chambered in the rounds, the rest of the companies dropped their projects and seeing as how everyone else dropped out, they too fell like dominoes and became too scared to be the first guinea pigs to test the new rounds in their rifles and see how well they'd sell.

There's a lot to say about marketability. As only a small percentage of guns ever become popular enough to reach the sale of thousands in the markets and "tried and true" gun designs have been around for over 100 years (the 1911, .50 caliber browning machine gun etc.), the ak-47 being around for over 70 years and the AR-15 over 60, it seems like gun manufacturers are typically afraid of anything new. That's why the initial reception of a cartridge, and it's adoption by various companies, is important for it's growth. Even if it's objectively better, even if it's more reliable or more accurate or more powerful, the simple fact that it's new and few companies are willing to take risks to their decade old platforms can kill a round or even a weapon before it even starts. Failure after failure after canceled military competition have taught the gun industry to be cautious, and to sell what sells rather than what is necessarily best. A 5,000 dollar SR-25 may be accurate, but it's hardly affordable, so to really make the big bucks you need something that can be mass produced and generally sold for under what a person is willing to pay. Past 1,500 dollars you find a lot of reservation for buying rifles, and depending on the rifle type this can be even lower, such as with Ak's (with most being under 1,000). Brand name is important as everyone and their mum's (and their mum's) are trying to sell an AR-15 derivative or a 1911, and a bad reputation, even with just a few guns, can kill a business. Reliability is one of the foremost concern of most consumers, second only to modularity and ergonomics. If the gun doesn't work reliably, if it can't be depended on, people won't want to use it. If it doesn't feel good to the hand, or it's just a bit heavy, a lot of guns will be ignored. Tiny factors can make or break the success of firearms, such as the AR-18 having the same weight and size as the AR-15, with the same recoil, but being more reliable and accurate, as well as cheaper and easier to maintain, but that for some unknown reason never achieved the popularity of the AR-15 or surpassed it. The gun industry is filled with great ideas that flopped due to poor marketing, and that become oddities of history asking ourselves "why don't we all use short stroke gas pistons?" or why didn't the AR-18 surpass the AR-15, the Galil the Ak etc. Companies are afraid to take risks, and for them to adopt a new round it can take quite a bit of investment.

It's just the reality of the situation. That's why the promotion of new, more promising designs or rounds need to be taken seriously, or at least seriously enough. While my personal favorites are the 6.5mm Grendel and 6.8mm Remington in the .223 replacement world, the .25-45 Sharp is a great contender, and will likely become the new most popular round. All that's needed for it to work is a barrel change. In the Tavor, this only takes a few minutes, for an AR-15, this only takes a few hours. For the Steyr Aug, this can only take a few seconds. Some weapons are even designed with quick detachable barrels, which makes replacing them much easier. The AR-15 for instance has it's barrel wear out after about 5,000 rounds, so it's designed to be replaced at least once during the lifetime of the firearm (usually 10,000 rounds). Barrels are then extremely easy to replace in most, but not all firearms, which makes them very, very easy for manufacturers to adopt. You drill a few holes and slots in a barrel to make it fit in the gun and, you've got a new barrel. In the case of the .300 black out and .25-45 sharp, the cartridge case is identical to shape and size to the 5.56mm; in fact in most cases, it literally uses 5.56mm or .223 cases. This means that the same magazines can be used, the same bolt, the same firing pin, the same trigger spring and basically everything else. The .300 black out and .25-45 sharp are literally just the same case of the .223 remington but "necked up" to use a larger cartridge. The brass lips where the bullet lies is literally just bent out wards to fit the new bullet in, which since brass is very soft and can stretch easily, is actually not very difficult to do. This means that everything on the guns, save for the barrel, can basically be identical as the chambering mechanisms on the bolt, the firing pin striking the primer etc. are all literally identical to the .223. The down side to using the same case as the 5.56mm is the diminished case capacity, especially with a larger round, and the requirement of using the same amount of powder. The .300 black out suffers from this especially so, only having 1800 joules with an 8 gram cartridge, which gives it a fairly low velocity of 670 m/s, which dramatically shortens the range of the round. While the bullet itself is nearly identical to the 7.62mm x 39mm in terms of size, it has 400 less joules, or 20% less energy, which dramatically impacts both the flight characteristics and power of the round. The best advantage of the .25-45 Sharp is that it utilizes newer gun powder, which far greater energies even from the exact same case, producing nearly 2,350 joules of energy.

More in depth Information

While the raw data can more or less be found here, the .25-45 sharp utilizes a slightly thicker brass case, giving it far greater strength, and uses much stronger and higher quality brass. This combined with the larger neck diameter, allows for greater power to be produced in the same cartridge size, without significantly increasing the internal pressure. The problem with superior gunpowder is that it tends to produce greater chamber pressures, which in turn puts more stress on the barrel and especially on guns not designed to withstand the pressure, can become dangerous. It's much better to have a cartridge with the same pressures as the bullet you're trying to shoot, so it doesn't endanger the user, and to do so requires simply superior gunpowder, which has more power for the same pressures. This may seem like a tall feat, to simply make gunpowder objectively better than other gunpowder, but it's not exactly a new thing. Gunpowder revolutions are quite common in the gun world. The original .45 ACP, now considered a relic of the past, was literally a .45 colt round designed to be shortened and using the more powerful cordite gunpowder of the time to allow it to feed reliably in semiautomatic weapons (hence the name "Automatic colt pistol", or ACP). At the time it was ground breaking technology, reducing the overall length of the case from 1.6 inches to 1.275 inches, and reducing the amount of powder needed for the same energy (500-600 joules) from 41 grains, to 25 grains. This made the cartridge both smaller and lighter, and produce less recoil for it's power (given the lower grain count and reduced weight of the brass which contributes partially to felt recoil), which made it more ideal for semiautomatic weapons. This may sound incredible, but just a few years later the 9mm parabellum, now the standard round for all of NATO, only uses 13 grams of gunpowder, compared to 25 grams to the .45 ACP, to produce the same amount of energy. The 9mm is around half the weight and size of the .45 ACP, with the case being even shorter at 1.169 inches. Now, some prefer the ballistics of the .45 ACP over the 9mm even though the case is smaller and more rounds can be fit in to a magazine, it's lighter weight and so on. So, the question has always come up; can we put this new and improved gun powder in the same cartridge, perhaps use some stronger brass in case it's too weak to handle the new pressures, and get the same results? The short answer is, yes! Absolutely. The .45 GAP for instance is such a round, widely used in glocks, producing the same energy or more as a standard .45 ACP, but being smaller and lighter, and using the same new and improved gun powder. But what if we kept the .45 ACP the same size? Kept the absolutely mammoth case and pumped it full of the most powerful gunpowder we could find? Well, you'd get the .45 super, which gets up to 1,000 joules worth of energy, equal to a .357 magnum, in fact exceeding the average cartridge. While only a handful of guns are designed to fire it, the HK45, HK USP, and a handful of 1911's can fire either the .45 or .45 super (albeit, ideally you would switch over the recoil spring before doing so), there are guns that can do so, meaning that yes, you can actually mix-and-match the gunpowder to whatever cartridge you want. There are very popular cartridges, such as the .45 ACP, that use such old gunpowder that new gunpowder can either shrink the size of the cartridge, or make it literally over twice as powerful. So after nearly 50 years, why not the .223?

While some have questioned the ability of the .25-45 Sharp to get approximately 30% greater power from the exact same case as the .223, this isn't exactly a new change in the firearms industry to have gunpowder improve, or some kind of secret that there's better gunpowder than what's found in many of the most popular cartridges. Every 20-30 years or so the gun industry goes through sweeping changes and the newest, best gun powder is used in new cartridges that are hailed as amazing inventions before they too are eventually replaced in the same manner. It wasn't that long ago that the .308 was the "new thing", replacing the older, and larger .30-06 cases that were nearly half an inch longer than the .308 with a much shorter and lighter round, ironically before it was replaced by the .223 which had more powerful gunpowder than the .308 and was even lighter and smaller than one might otherwise think. In fact during the life of the .223, the change in gunpowder shifted from a round producing 1300 joules initially, to one producing 1800 joules, or being nearly 35% more powerful, with the military shifting to this more powerful ammunition. Since the .223 is nearly 50 years old and the military has been reluctant to replace it's somewhat aging rifles (the springfield was replaced in 33 years by the M1 garand, the M1 garand was replaced in 23 years, the M14 in 16 years, and the M16 is still in service after nearly 50 years, or 46 years of official adoption), it was bound to have some cartridges that proved to, objectively, be more powerful for their overall size. If we use the .223's level of energy of 1,800 joules from a 20 inch barrel as our baseline, than in comparison the 6.5mm Grendel produces approximately 2,600 joules, the 6.8mm Remington 2,700, and the .24-45 sharp 2,350. An Ak-47 by comparison has about 2,200 joules, and is notoriously more powerful than the 5.56mm, having an easier time passing through common barriers such as cinder blocks and brick walls. So, the primary drawback of the .223 has always been it's rather lack luster power and small size, but the .25-45 sharp produces far greater energies than it, or even the Ak-47. The .25-45 sharp can give the Ak-47 a run for it's money in terms of energy. Even better, the .25-45 sharp is a much heavier cartridge than the .223, ranging between 5.6 and 7 grams in terms of weight (compared to the Ak-47 at 8 grams), compared to the 3.6 to 5 gram weight of the .223. Until recently, few .223 bullets existed with a BC above .3, and the best so far has a BC of approximate.y .35 G1, or the blackhills Mk. 262 77 grain, boat-tail hollow point ammunition, currently used by U.S. snipers. While certainly an excellent cartridge, the navy seals and other users found it to be a bit lack luster ,and moved to replaced their special purpose (SPR) 5.56mm marksmen rifles, largely citing it's lack of power, especially at long ranges, as their primary concerns.

There have been a lot of arguments in terms of the theoretical power of various bullets, particularly in regards to the .223 compared to the .25-45. Arguably, a larger bullet means less case capacity as being more deeply seated in to the cartridge decreases how many grains of powder can be stored in it. And in theory a smaller bullet should have less aerodynamic resistance when in flight. Yet, neither of these two things are true in reality. The question eventually comes, why would we choose to use the 6mm or 6.5mm over the 5.56mm and not just use a 2,350 joule .223 and not have to change the barrel at all? (which is, of course, theoretically possible). There are quite a few factors that influence this, which can be summarized as: the first factor being the weak nature of the .223 in general, the second being the case more deeply seated in to the cartridge doesn't impact the energy enough to make a realistic difference, the third being that better more aerodynamic cartridges exist which can be chambered in the round so it might as well be done, the fourth being that the barrel twist of the barrel would have to change anyway with a higher velocity round necessitating a switch, and the fifth simply being that a larger neck diameter reduces maximum chamber pressures even if using the same gunpowder. The first is perhaps the most obvious, which is that the .223 is tiny. The small size not only dramatically reduces the power of the cartridge, but also it's long range capabilities. While many would presume that a higher velocity round would automatically have a longer range (if it's faster, it can travel farther, right?), but the faster a bullet goes the more aerodynamic resistance it experiences. Further, bullets have a tendency to lose energy over time due to a loss in momentum and force. The heavier a bullet is, the more momentum and inertia it has, and the harder it is for it to lose energy. Nearly all sniper rounds increase the weight and reduce the velocity of the round. Be it the black hills ammunition going from 4.1 grams to 5 grams with the .223, or the Sniper 7.62mm x 51mm rounds going from 9.7 grams to 11.3 grams, nearly all sniper bullets are slightly heavier than the lighter counter parts. This gives a better range due to less energy lost in the first few hundred yards, and of course a greater momentum and greater power at terminal ranges given the less-velocity dependent cartridge. The ideal sniper cartridge also tends to have a velocity between 750 m/s and 850 m/s, meaning that extremely high velocities don't seem to be relevant; the .308, .223, even the .50 cal's best sniper rounds are between this butter zone. The fact the 6.5mm, 6.8mm, and .25-45 sharp are in this zone makes the round more promising, not less so. Imagine trying to throw a paper ball as fast as you could compared to a marble, or a baseball. It's light weight means it starts off faster,but this is actually a hindrance as the exponential loss of energy in the close range coupled with it's even lower momentum allows it to waste most of it's energy; throwing a paper ball really hard will actually make it go a shorter distance than if you throw it softer, and the same is true with a paper airplane. There's as stated before a certain butter zone for most rounds. For instance, in 100 yards a 5.56mm from a full-length barrel will go from 1,800 joules to 1,445, losing 20% of it's energy at relatively close engagement ranges. At 300 yards, it's lost approximately half of it's energy, or dropped down to 900 joules, making it lose effectiveness from the already weak cartridge. A 2009 study conducted by the U.S. Army claimed that half of the engagements in Afghanistan occurred from beyond 300 meters (330 yd). America's 5.56×45mm NATO service rifles were determined to be ineffective at these ranges, which prompted the reissue of thousands of M14s. As engagement distances in Afghanistan could reach up to 800 yards, the loss of energy with the 5.56mm was considered serious enough for hasty production and fielding of M14's to begin. At 600 yards the 5.56mm only possesses around 420 joules, or loses nearly 350% of it's energy. With a 4 gram round, it's akin to being hit by a piece of shrapnel, and has trouble penetrating armor. At 900 yards, according to the U.S. military the weapon loses it's lethality entirely. To say that the 5.56mm has an effective range of 600 yards is like saying the 7.62mm x 51mm NATO has an effective range of 1200 yards. There are few confirmed kills past 1,000 yards with the .308 (or 600 with the 5.56mm), and even fewer at 1,200. While some might question why an intermediate cartridge such as the 6.5mm Grendel or .25-45 sharp that can get out to 600 yards is really such a unique or important capability, as the 5.56mm is a 600 yard gun, the simple reality is that the 5.56mm just does not do well at 600 yards, or even past 300 yards. A 600 yard shot with the 5.56mm is akin to a unicorn sighting, something talked about and heard of, but rarely if ever actually seen. True, realistic 600+ yard engagements require substantially better rounds, and this is confirmed by nearly every experienced shooter and the military. Essentially, these rounds offer far greater long range ability, which allows the users to fullfill both a marksmen and riflemen role. Every marine a riflemen, now it could be every riflemen a marksmen.

Secondly, a more deeply seated round in the case provides two advantages, one being that it can get greater energy transfer to the round allowing it to quixotically gain back some lost energy, and a longer overall bullet. Increasing the ballistic coefficient of a bullet usually requires making it longer, as the longer it is, the less aerodynamic resistance it possesses. A very thin piece of material spread out over a longer area produces more aerodynamic resistance, such as a kite or a parachute. There's a reason gliders use very thin materials, and that's to make it capable of catching the air so it can fly. On the other hand, when you want something to ignore air, you want it to be very thick and have a small surface area facing the direction of the air or wind. A bullet is pointed and cylindrical so that way when it faces the air, it can cut through it rather than capture the air. The longer the bullet, the more mass you can fit in with a lower surface area facing the wind. Other properties to aerodynamics don't have to do with reducing drag, but stabilizing the bullet in flight. A boat tail hollowpoint with a small cavity in the nose allows for greater stability, by forming small air pockets which help to redirect the air, which in turn makes it more accurate. Typically to take advantage of this, you need a longer, skinnier bullet. The diameter of the bullet matters less than the length of the bullet. So while a really small bullet such as a .223 may seem to have better aerodynamics in theory, in practice the larger a bullet gets, generally the more aerodynamic it becomes. You only need to look at the .338 lapua. .300 win mag, .50 caliber rifle rounds or even any sniper round used by the military to realize that the idea that a smaller bullet always means better aerodynamics is more than a bit farcical. Some bullets even use plastic tips or plastic pieces to increase the aerodynamic properties of the bullet without removing the shape of the bullet that might result in better lethality or barrier penetration (such as a hollow point). The average military 5.56mm, or the M855, has a G1 BC of approximately .2. The Mk. 262 has a G1 BC of approximately .36 BC. The average .25-45 Sharp has a BC of .3, but it can go up to .425 with the right 6mm rounds. The 6.5mm Grendel has a BC of .48 to .53, where as .308 sniper rounds typically have a BC of around the same. A .50 caliber sniper round has a BC of 1.050. Literally over 1 BC, or ballistic coefficient. So, the larger the round is, usually the better long range ballistics it will have, even though quixotically we would assume the exact opposite. It takes considerably more expensive to make a smaller round more aerodynamic, due to it's lower sectional density. The average 6.8mm Remington for instance has a BC of approximately .35, as do most of the .24-45 sharp rounds. While these rounds are around 35 cents to 50 cents, the Mk. 262 ammo is typically up to a dollar, but they can be found for around the same price at the upper levels. They're generally cheaper and easier to mass produce, as well as more accurate on average, meaning that it's a superior cartridge not with match grade ammunition compared to each other, but average rounds. These rounds all outperform match grade .223 ammunition, and blow regular, military surplus ammunition out of the water. But ignoring the price, let's see how they compare at their extremes.

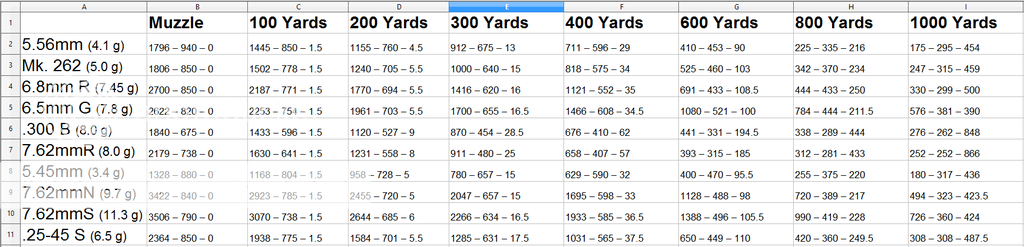

The Mk. 262 is a fine round, but due to the inherent power and size of the .25-45 sharp, simply cannot reach it's levels. The .25-45 sharp completely blows away the the standard M855 ball, as well. For the sake of brevity I'll compare the energy levels of two variants of the .25-45 sharp to two variants of .223 ammunition, at 100, 300, and 600 yards respectively. The .223 gets 1800 joules at the muzzle from a full length barrel, compared to 2350 for the .25-45 sharp. The M855 and Mk. 262 have 1445 and 1502 joules at 100 yards, 912 and 1000 joules at 300 yards, and 410 and 525 joules at 600 yards, respectively. Energy obviously isn't the only factor to consider, as a heavier round tends to have more stopping power, especially at longer ranges. Even so, both .25-45 sharp rounds have approximately 2,350 joules at the muzzle, with the 87 grain -5.6 gram round having a BC of .3 and the 100 grain-6.5 gram round having a BC of .425. At 100 yards the rounds have an energy of 1938 and 1884 joules, 1285 and 1175 joules at 300 yards, and 650 and 533 joules at 600 yards. As you can see, at their respective ranges the .25-45 sharp have way more energy than the 5.56mm; the weapon has more energy than the 5.56mm at 100 yards than the 5.56mm does at the muzzle, and being much heavier it hits with greater force and has more ideal barrier penetration. Even the lightest variant is heavier than the Mk. 262 ammunition, and has around the same ballistic coefficient. The rounds pierce armor slightly better and generally are more powerful. These rounds tend to only have 10% greater recoil, and are only a few grams heavier, dependent on the weight of the bullet, making less than 15% heavier, with the same magazine capacity from the same magazines. In comparison the 6.5mm Grendel has roughly double the recoil and is about 30% heavier, but has 2,600 joules at the muzzle, 2253 at 100 yards, 1700 at 300 yards, and 1080 at 600 yard. This gives it the energy and mass of a .357 magnum at 600 yards, with better penetration, and nearly the same energy as the .223 or .300 black-out at 300 yards as they do at the muzzle. It's so aerodynamic in fact that it surpasses the .308 at these ranges despite a nearly 1,000 joule difference in starting energy.

Of course, to change any 5.56mm firearm to the .25-45 sharp all you need to do is swap out the barrel. No magazine changes, no springs, certainly not a bolt, nothing but the barrel, unlike with the grendel. While the 6.5mm Grendel has a longer range and more power and the 6.8mm remington does better from a shorter barrel, neither round can be this easily converted to. It gives the power of an Ak-47 in any 5.56mm gun, but a longer range, more aerodynamic bullet, with characteristics more suited for a riflemen. It not only has more punch but does so at a longer range, making it good for long range target shooting. While it is far from a perfect round, it's ability to fit in any 5.56mm weapon means that it can be very easily converted to fire it. Unlike the .300 black-out which is more of a novelty round that is less powerful than an Ak without the accuracy and range of the 5.56mm, the .25-45 sharp exceeds both the .223 and 7.62mm x 39mm, all without even changing the case and with very little change in recoil and weight. For this and other reasons, it is my opinion that it should become the new, best "AR" conversion round, being easy to convert and substantially more powerful.

So, there's been quite a few new AR rounds out there or, .223 replacements. The 6.5mm Grendel, the 6.8mm Remington, the .300 black-out, the .458 SOCOM (which is actually an old round, but it's making a come-back) and numerous others designed to work inside of a gun more or less designed to fire the .223 or 5.56mm x 45mm NATO, without many modifications. The receiver of the gun, the legal part of the gun, and arguably the hardest part to make and recreate, can be used as well as the magazines with all these rounds, but the bolt, the recoil spring and the barrel often need to be replaced, which are fairly easy to replace on most firearms. Especially with the AR, which has an easily detachable barrel, it's easy modify these weapons to be able to accept and fire the rounds by changing out the bolt, the spring and the barrel. In the case of the .300 black-out and .25-45 sharps, all that needs to be replaced is, the barrel. According to some however, the .25-45 sharp is the worst new AR round, and the Mk. 262 far surpasses it and the 6.8mm Remington. I simply disagree.

What makes the .25-45 Sharps so promising is that unlike the 6.8mm Remington or 6.5mm Grendel which are objectivity more powerful and longer range rounds, is as mentioned before, that only the barrel needs to be replaced. Designing, creating and fitting in an entirely new bolt and recoil spring is apparently rather difficult for most firearms manufacturers, albeit theoretically possible. The ACR, or Remington Advanced Combat Rifle, was originally promised to be chambered in numerous rounds, from the 6.8mm to the 7.62mm x 39mm, but never was actually mass produced in any caliber other than the 5.56mm. After over 5 years since being announced, the 7.62mm x 51mm NATO and other variants of the rifle have yet to come to fruition, and seem to be little more than vapor ware. The FN SCAR, Tavor and numerous other companies have promised caliber version after caliber version, and as of yet only a single 6.5mm Grendel and a handful of 6.8mm Remington firearms even exist for sale, largely AR-15 variants. Apparently designing a new bolt, which is simple in theory, is far more complicated in practice. Likely, the size of the new rounds means the bolts have to be enlarged and a new hole has to be drilled in the bolt carrier to fit the new balanced bolt, or the bolt has to be asymmetrically placed which would put a lot of stress on the gun and possibly limit reliability. It's far more likely that company executives simply did a tally of the popularity of the cartridge, realized the profits wouldn't be worth the money spent and scrapped the project after they realized their money could be better spent for higher profits. Gun manufacturers are a finicky lot, and with every gun ban scare you get huge fluctuations in prices from ammo to guns, manufacturers changing processes even before the ban gets passed (which it might actually never), company head quarters changing and generally the tiniest tremors, like a pebble in a pond, can create gigantic shock waves through the industry. Most likely, as no other company was producing rifles chambered in the rounds, the rest of the companies dropped their projects and seeing as how everyone else dropped out, they too fell like dominoes and became too scared to be the first guinea pigs to test the new rounds in their rifles and see how well they'd sell.

There's a lot to say about marketability. As only a small percentage of guns ever become popular enough to reach the sale of thousands in the markets and "tried and true" gun designs have been around for over 100 years (the 1911, .50 caliber browning machine gun etc.), the ak-47 being around for over 70 years and the AR-15 over 60, it seems like gun manufacturers are typically afraid of anything new. That's why the initial reception of a cartridge, and it's adoption by various companies, is important for it's growth. Even if it's objectively better, even if it's more reliable or more accurate or more powerful, the simple fact that it's new and few companies are willing to take risks to their decade old platforms can kill a round or even a weapon before it even starts. Failure after failure after canceled military competition have taught the gun industry to be cautious, and to sell what sells rather than what is necessarily best. A 5,000 dollar SR-25 may be accurate, but it's hardly affordable, so to really make the big bucks you need something that can be mass produced and generally sold for under what a person is willing to pay. Past 1,500 dollars you find a lot of reservation for buying rifles, and depending on the rifle type this can be even lower, such as with Ak's (with most being under 1,000). Brand name is important as everyone and their mum's (and their mum's) are trying to sell an AR-15 derivative or a 1911, and a bad reputation, even with just a few guns, can kill a business. Reliability is one of the foremost concern of most consumers, second only to modularity and ergonomics. If the gun doesn't work reliably, if it can't be depended on, people won't want to use it. If it doesn't feel good to the hand, or it's just a bit heavy, a lot of guns will be ignored. Tiny factors can make or break the success of firearms, such as the AR-18 having the same weight and size as the AR-15, with the same recoil, but being more reliable and accurate, as well as cheaper and easier to maintain, but that for some unknown reason never achieved the popularity of the AR-15 or surpassed it. The gun industry is filled with great ideas that flopped due to poor marketing, and that become oddities of history asking ourselves "why don't we all use short stroke gas pistons?" or why didn't the AR-18 surpass the AR-15, the Galil the Ak etc. Companies are afraid to take risks, and for them to adopt a new round it can take quite a bit of investment.

It's just the reality of the situation. That's why the promotion of new, more promising designs or rounds need to be taken seriously, or at least seriously enough. While my personal favorites are the 6.5mm Grendel and 6.8mm Remington in the .223 replacement world, the .25-45 Sharp is a great contender, and will likely become the new most popular round. All that's needed for it to work is a barrel change. In the Tavor, this only takes a few minutes, for an AR-15, this only takes a few hours. For the Steyr Aug, this can only take a few seconds. Some weapons are even designed with quick detachable barrels, which makes replacing them much easier. The AR-15 for instance has it's barrel wear out after about 5,000 rounds, so it's designed to be replaced at least once during the lifetime of the firearm (usually 10,000 rounds). Barrels are then extremely easy to replace in most, but not all firearms, which makes them very, very easy for manufacturers to adopt. You drill a few holes and slots in a barrel to make it fit in the gun and, you've got a new barrel. In the case of the .300 black out and .25-45 sharp, the cartridge case is identical to shape and size to the 5.56mm; in fact in most cases, it literally uses 5.56mm or .223 cases. This means that the same magazines can be used, the same bolt, the same firing pin, the same trigger spring and basically everything else. The .300 black out and .25-45 sharp are literally just the same case of the .223 remington but "necked up" to use a larger cartridge. The brass lips where the bullet lies is literally just bent out wards to fit the new bullet in, which since brass is very soft and can stretch easily, is actually not very difficult to do. This means that everything on the guns, save for the barrel, can basically be identical as the chambering mechanisms on the bolt, the firing pin striking the primer etc. are all literally identical to the .223. The down side to using the same case as the 5.56mm is the diminished case capacity, especially with a larger round, and the requirement of using the same amount of powder. The .300 black out suffers from this especially so, only having 1800 joules with an 8 gram cartridge, which gives it a fairly low velocity of 670 m/s, which dramatically shortens the range of the round. While the bullet itself is nearly identical to the 7.62mm x 39mm in terms of size, it has 400 less joules, or 20% less energy, which dramatically impacts both the flight characteristics and power of the round. The best advantage of the .25-45 Sharp is that it utilizes newer gun powder, which far greater energies even from the exact same case, producing nearly 2,350 joules of energy.

More in depth Information

While the raw data can more or less be found here, the .25-45 sharp utilizes a slightly thicker brass case, giving it far greater strength, and uses much stronger and higher quality brass. This combined with the larger neck diameter, allows for greater power to be produced in the same cartridge size, without significantly increasing the internal pressure. The problem with superior gunpowder is that it tends to produce greater chamber pressures, which in turn puts more stress on the barrel and especially on guns not designed to withstand the pressure, can become dangerous. It's much better to have a cartridge with the same pressures as the bullet you're trying to shoot, so it doesn't endanger the user, and to do so requires simply superior gunpowder, which has more power for the same pressures. This may seem like a tall feat, to simply make gunpowder objectively better than other gunpowder, but it's not exactly a new thing. Gunpowder revolutions are quite common in the gun world. The original .45 ACP, now considered a relic of the past, was literally a .45 colt round designed to be shortened and using the more powerful cordite gunpowder of the time to allow it to feed reliably in semiautomatic weapons (hence the name "Automatic colt pistol", or ACP). At the time it was ground breaking technology, reducing the overall length of the case from 1.6 inches to 1.275 inches, and reducing the amount of powder needed for the same energy (500-600 joules) from 41 grains, to 25 grains. This made the cartridge both smaller and lighter, and produce less recoil for it's power (given the lower grain count and reduced weight of the brass which contributes partially to felt recoil), which made it more ideal for semiautomatic weapons. This may sound incredible, but just a few years later the 9mm parabellum, now the standard round for all of NATO, only uses 13 grams of gunpowder, compared to 25 grams to the .45 ACP, to produce the same amount of energy. The 9mm is around half the weight and size of the .45 ACP, with the case being even shorter at 1.169 inches. Now, some prefer the ballistics of the .45 ACP over the 9mm even though the case is smaller and more rounds can be fit in to a magazine, it's lighter weight and so on. So, the question has always come up; can we put this new and improved gun powder in the same cartridge, perhaps use some stronger brass in case it's too weak to handle the new pressures, and get the same results? The short answer is, yes! Absolutely. The .45 GAP for instance is such a round, widely used in glocks, producing the same energy or more as a standard .45 ACP, but being smaller and lighter, and using the same new and improved gun powder. But what if we kept the .45 ACP the same size? Kept the absolutely mammoth case and pumped it full of the most powerful gunpowder we could find? Well, you'd get the .45 super, which gets up to 1,000 joules worth of energy, equal to a .357 magnum, in fact exceeding the average cartridge. While only a handful of guns are designed to fire it, the HK45, HK USP, and a handful of 1911's can fire either the .45 or .45 super (albeit, ideally you would switch over the recoil spring before doing so), there are guns that can do so, meaning that yes, you can actually mix-and-match the gunpowder to whatever cartridge you want. There are very popular cartridges, such as the .45 ACP, that use such old gunpowder that new gunpowder can either shrink the size of the cartridge, or make it literally over twice as powerful. So after nearly 50 years, why not the .223?

While some have questioned the ability of the .25-45 Sharp to get approximately 30% greater power from the exact same case as the .223, this isn't exactly a new change in the firearms industry to have gunpowder improve, or some kind of secret that there's better gunpowder than what's found in many of the most popular cartridges. Every 20-30 years or so the gun industry goes through sweeping changes and the newest, best gun powder is used in new cartridges that are hailed as amazing inventions before they too are eventually replaced in the same manner. It wasn't that long ago that the .308 was the "new thing", replacing the older, and larger .30-06 cases that were nearly half an inch longer than the .308 with a much shorter and lighter round, ironically before it was replaced by the .223 which had more powerful gunpowder than the .308 and was even lighter and smaller than one might otherwise think. In fact during the life of the .223, the change in gunpowder shifted from a round producing 1300 joules initially, to one producing 1800 joules, or being nearly 35% more powerful, with the military shifting to this more powerful ammunition. Since the .223 is nearly 50 years old and the military has been reluctant to replace it's somewhat aging rifles (the springfield was replaced in 33 years by the M1 garand, the M1 garand was replaced in 23 years, the M14 in 16 years, and the M16 is still in service after nearly 50 years, or 46 years of official adoption), it was bound to have some cartridges that proved to, objectively, be more powerful for their overall size. If we use the .223's level of energy of 1,800 joules from a 20 inch barrel as our baseline, than in comparison the 6.5mm Grendel produces approximately 2,600 joules, the 6.8mm Remington 2,700, and the .24-45 sharp 2,350. An Ak-47 by comparison has about 2,200 joules, and is notoriously more powerful than the 5.56mm, having an easier time passing through common barriers such as cinder blocks and brick walls. So, the primary drawback of the .223 has always been it's rather lack luster power and small size, but the .25-45 sharp produces far greater energies than it, or even the Ak-47. The .25-45 sharp can give the Ak-47 a run for it's money in terms of energy. Even better, the .25-45 sharp is a much heavier cartridge than the .223, ranging between 5.6 and 7 grams in terms of weight (compared to the Ak-47 at 8 grams), compared to the 3.6 to 5 gram weight of the .223. Until recently, few .223 bullets existed with a BC above .3, and the best so far has a BC of approximate.y .35 G1, or the blackhills Mk. 262 77 grain, boat-tail hollow point ammunition, currently used by U.S. snipers. While certainly an excellent cartridge, the navy seals and other users found it to be a bit lack luster ,and moved to replaced their special purpose (SPR) 5.56mm marksmen rifles, largely citing it's lack of power, especially at long ranges, as their primary concerns.

There have been a lot of arguments in terms of the theoretical power of various bullets, particularly in regards to the .223 compared to the .25-45. Arguably, a larger bullet means less case capacity as being more deeply seated in to the cartridge decreases how many grains of powder can be stored in it. And in theory a smaller bullet should have less aerodynamic resistance when in flight. Yet, neither of these two things are true in reality. The question eventually comes, why would we choose to use the 6mm or 6.5mm over the 5.56mm and not just use a 2,350 joule .223 and not have to change the barrel at all? (which is, of course, theoretically possible). There are quite a few factors that influence this, which can be summarized as: the first factor being the weak nature of the .223 in general, the second being the case more deeply seated in to the cartridge doesn't impact the energy enough to make a realistic difference, the third being that better more aerodynamic cartridges exist which can be chambered in the round so it might as well be done, the fourth being that the barrel twist of the barrel would have to change anyway with a higher velocity round necessitating a switch, and the fifth simply being that a larger neck diameter reduces maximum chamber pressures even if using the same gunpowder. The first is perhaps the most obvious, which is that the .223 is tiny. The small size not only dramatically reduces the power of the cartridge, but also it's long range capabilities. While many would presume that a higher velocity round would automatically have a longer range (if it's faster, it can travel farther, right?), but the faster a bullet goes the more aerodynamic resistance it experiences. Further, bullets have a tendency to lose energy over time due to a loss in momentum and force. The heavier a bullet is, the more momentum and inertia it has, and the harder it is for it to lose energy. Nearly all sniper rounds increase the weight and reduce the velocity of the round. Be it the black hills ammunition going from 4.1 grams to 5 grams with the .223, or the Sniper 7.62mm x 51mm rounds going from 9.7 grams to 11.3 grams, nearly all sniper bullets are slightly heavier than the lighter counter parts. This gives a better range due to less energy lost in the first few hundred yards, and of course a greater momentum and greater power at terminal ranges given the less-velocity dependent cartridge. The ideal sniper cartridge also tends to have a velocity between 750 m/s and 850 m/s, meaning that extremely high velocities don't seem to be relevant; the .308, .223, even the .50 cal's best sniper rounds are between this butter zone. The fact the 6.5mm, 6.8mm, and .25-45 sharp are in this zone makes the round more promising, not less so. Imagine trying to throw a paper ball as fast as you could compared to a marble, or a baseball. It's light weight means it starts off faster,but this is actually a hindrance as the exponential loss of energy in the close range coupled with it's even lower momentum allows it to waste most of it's energy; throwing a paper ball really hard will actually make it go a shorter distance than if you throw it softer, and the same is true with a paper airplane. There's as stated before a certain butter zone for most rounds. For instance, in 100 yards a 5.56mm from a full-length barrel will go from 1,800 joules to 1,445, losing 20% of it's energy at relatively close engagement ranges. At 300 yards, it's lost approximately half of it's energy, or dropped down to 900 joules, making it lose effectiveness from the already weak cartridge. A 2009 study conducted by the U.S. Army claimed that half of the engagements in Afghanistan occurred from beyond 300 meters (330 yd). America's 5.56×45mm NATO service rifles were determined to be ineffective at these ranges, which prompted the reissue of thousands of M14s. As engagement distances in Afghanistan could reach up to 800 yards, the loss of energy with the 5.56mm was considered serious enough for hasty production and fielding of M14's to begin. At 600 yards the 5.56mm only possesses around 420 joules, or loses nearly 350% of it's energy. With a 4 gram round, it's akin to being hit by a piece of shrapnel, and has trouble penetrating armor. At 900 yards, according to the U.S. military the weapon loses it's lethality entirely. To say that the 5.56mm has an effective range of 600 yards is like saying the 7.62mm x 51mm NATO has an effective range of 1200 yards. There are few confirmed kills past 1,000 yards with the .308 (or 600 with the 5.56mm), and even fewer at 1,200. While some might question why an intermediate cartridge such as the 6.5mm Grendel or .25-45 sharp that can get out to 600 yards is really such a unique or important capability, as the 5.56mm is a 600 yard gun, the simple reality is that the 5.56mm just does not do well at 600 yards, or even past 300 yards. A 600 yard shot with the 5.56mm is akin to a unicorn sighting, something talked about and heard of, but rarely if ever actually seen. True, realistic 600+ yard engagements require substantially better rounds, and this is confirmed by nearly every experienced shooter and the military. Essentially, these rounds offer far greater long range ability, which allows the users to fullfill both a marksmen and riflemen role. Every marine a riflemen, now it could be every riflemen a marksmen.

Secondly, a more deeply seated round in the case provides two advantages, one being that it can get greater energy transfer to the round allowing it to quixotically gain back some lost energy, and a longer overall bullet. Increasing the ballistic coefficient of a bullet usually requires making it longer, as the longer it is, the less aerodynamic resistance it possesses. A very thin piece of material spread out over a longer area produces more aerodynamic resistance, such as a kite or a parachute. There's a reason gliders use very thin materials, and that's to make it capable of catching the air so it can fly. On the other hand, when you want something to ignore air, you want it to be very thick and have a small surface area facing the direction of the air or wind. A bullet is pointed and cylindrical so that way when it faces the air, it can cut through it rather than capture the air. The longer the bullet, the more mass you can fit in with a lower surface area facing the wind. Other properties to aerodynamics don't have to do with reducing drag, but stabilizing the bullet in flight. A boat tail hollowpoint with a small cavity in the nose allows for greater stability, by forming small air pockets which help to redirect the air, which in turn makes it more accurate. Typically to take advantage of this, you need a longer, skinnier bullet. The diameter of the bullet matters less than the length of the bullet. So while a really small bullet such as a .223 may seem to have better aerodynamics in theory, in practice the larger a bullet gets, generally the more aerodynamic it becomes. You only need to look at the .338 lapua. .300 win mag, .50 caliber rifle rounds or even any sniper round used by the military to realize that the idea that a smaller bullet always means better aerodynamics is more than a bit farcical. Some bullets even use plastic tips or plastic pieces to increase the aerodynamic properties of the bullet without removing the shape of the bullet that might result in better lethality or barrier penetration (such as a hollow point). The average military 5.56mm, or the M855, has a G1 BC of approximately .2. The Mk. 262 has a G1 BC of approximately .36 BC. The average .25-45 Sharp has a BC of .3, but it can go up to .425 with the right 6mm rounds. The 6.5mm Grendel has a BC of .48 to .53, where as .308 sniper rounds typically have a BC of around the same. A .50 caliber sniper round has a BC of 1.050. Literally over 1 BC, or ballistic coefficient. So, the larger the round is, usually the better long range ballistics it will have, even though quixotically we would assume the exact opposite. It takes considerably more expensive to make a smaller round more aerodynamic, due to it's lower sectional density. The average 6.8mm Remington for instance has a BC of approximately .35, as do most of the .24-45 sharp rounds. While these rounds are around 35 cents to 50 cents, the Mk. 262 ammo is typically up to a dollar, but they can be found for around the same price at the upper levels. They're generally cheaper and easier to mass produce, as well as more accurate on average, meaning that it's a superior cartridge not with match grade ammunition compared to each other, but average rounds. These rounds all outperform match grade .223 ammunition, and blow regular, military surplus ammunition out of the water. But ignoring the price, let's see how they compare at their extremes.

The Mk. 262 is a fine round, but due to the inherent power and size of the .25-45 sharp, simply cannot reach it's levels. The .25-45 sharp completely blows away the the standard M855 ball, as well. For the sake of brevity I'll compare the energy levels of two variants of the .25-45 sharp to two variants of .223 ammunition, at 100, 300, and 600 yards respectively. The .223 gets 1800 joules at the muzzle from a full length barrel, compared to 2350 for the .25-45 sharp. The M855 and Mk. 262 have 1445 and 1502 joules at 100 yards, 912 and 1000 joules at 300 yards, and 410 and 525 joules at 600 yards, respectively. Energy obviously isn't the only factor to consider, as a heavier round tends to have more stopping power, especially at longer ranges. Even so, both .25-45 sharp rounds have approximately 2,350 joules at the muzzle, with the 87 grain -5.6 gram round having a BC of .3 and the 100 grain-6.5 gram round having a BC of .425. At 100 yards the rounds have an energy of 1938 and 1884 joules, 1285 and 1175 joules at 300 yards, and 650 and 533 joules at 600 yards. As you can see, at their respective ranges the .25-45 sharp have way more energy than the 5.56mm; the weapon has more energy than the 5.56mm at 100 yards than the 5.56mm does at the muzzle, and being much heavier it hits with greater force and has more ideal barrier penetration. Even the lightest variant is heavier than the Mk. 262 ammunition, and has around the same ballistic coefficient. The rounds pierce armor slightly better and generally are more powerful. These rounds tend to only have 10% greater recoil, and are only a few grams heavier, dependent on the weight of the bullet, making less than 15% heavier, with the same magazine capacity from the same magazines. In comparison the 6.5mm Grendel has roughly double the recoil and is about 30% heavier, but has 2,600 joules at the muzzle, 2253 at 100 yards, 1700 at 300 yards, and 1080 at 600 yard. This gives it the energy and mass of a .357 magnum at 600 yards, with better penetration, and nearly the same energy as the .223 or .300 black-out at 300 yards as they do at the muzzle. It's so aerodynamic in fact that it surpasses the .308 at these ranges despite a nearly 1,000 joule difference in starting energy.

Of course, to change any 5.56mm firearm to the .25-45 sharp all you need to do is swap out the barrel. No magazine changes, no springs, certainly not a bolt, nothing but the barrel, unlike with the grendel. While the 6.5mm Grendel has a longer range and more power and the 6.8mm remington does better from a shorter barrel, neither round can be this easily converted to. It gives the power of an Ak-47 in any 5.56mm gun, but a longer range, more aerodynamic bullet, with characteristics more suited for a riflemen. It not only has more punch but does so at a longer range, making it good for long range target shooting. While it is far from a perfect round, it's ability to fit in any 5.56mm weapon means that it can be very easily converted to fire it. Unlike the .300 black-out which is more of a novelty round that is less powerful than an Ak without the accuracy and range of the 5.56mm, the .25-45 sharp exceeds both the .223 and 7.62mm x 39mm, all without even changing the case and with very little change in recoil and weight. For this and other reasons, it is my opinion that it should become the new, best "AR" conversion round, being easy to convert and substantially more powerful.

Comments

Post a Comment